Language Brief: Arabic

Written by Laura Henry, Linguistic AnalystThe word for the Arabic language (العربية, al-`Arabiyya) written in Arabic.

Helpful Info for Employers

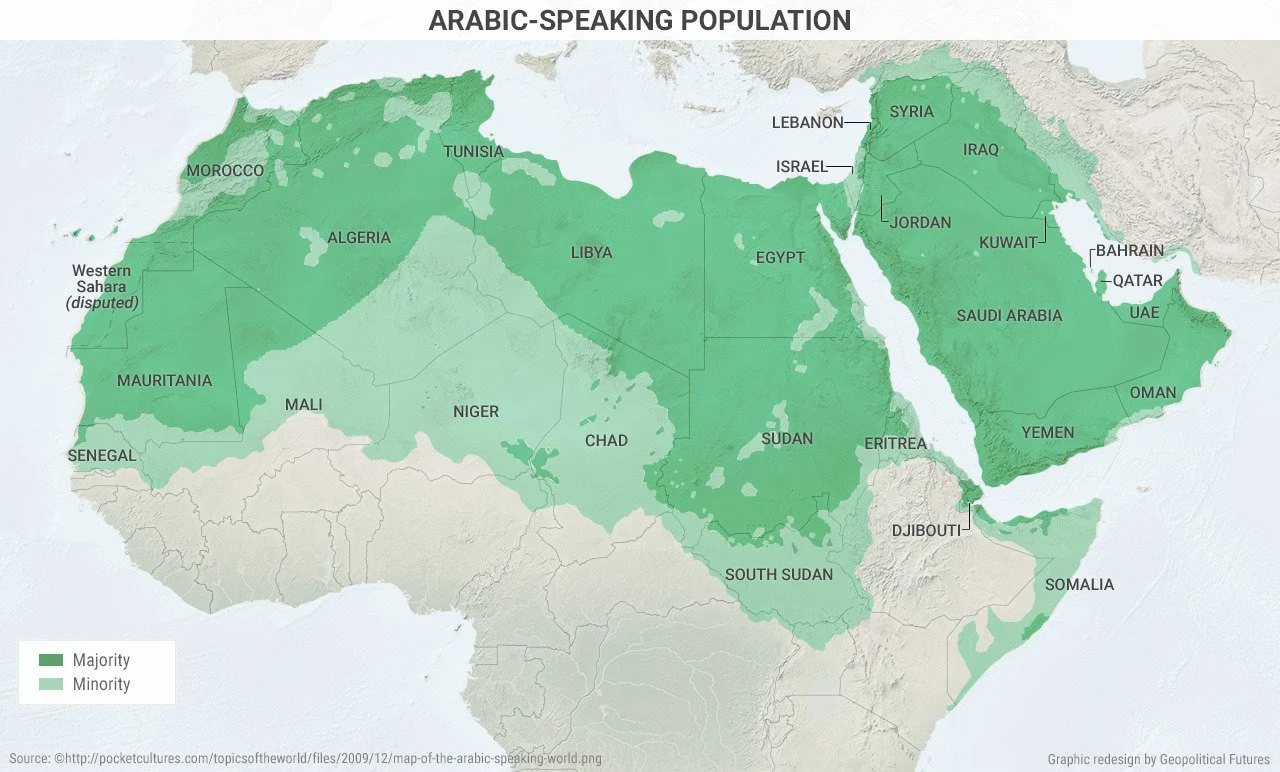

Arabic is one of the five most commonly spoken languages in the world, with approximately 350 million native speakers and 70 million non-native speakers primarily located in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, and other parts of the Middle East. It is the lingua franca of the region, meaning that it is a language that is shared by multiple countries and territories in the area.

What are the different “versions” of Arabic?

Source: ResearchGate

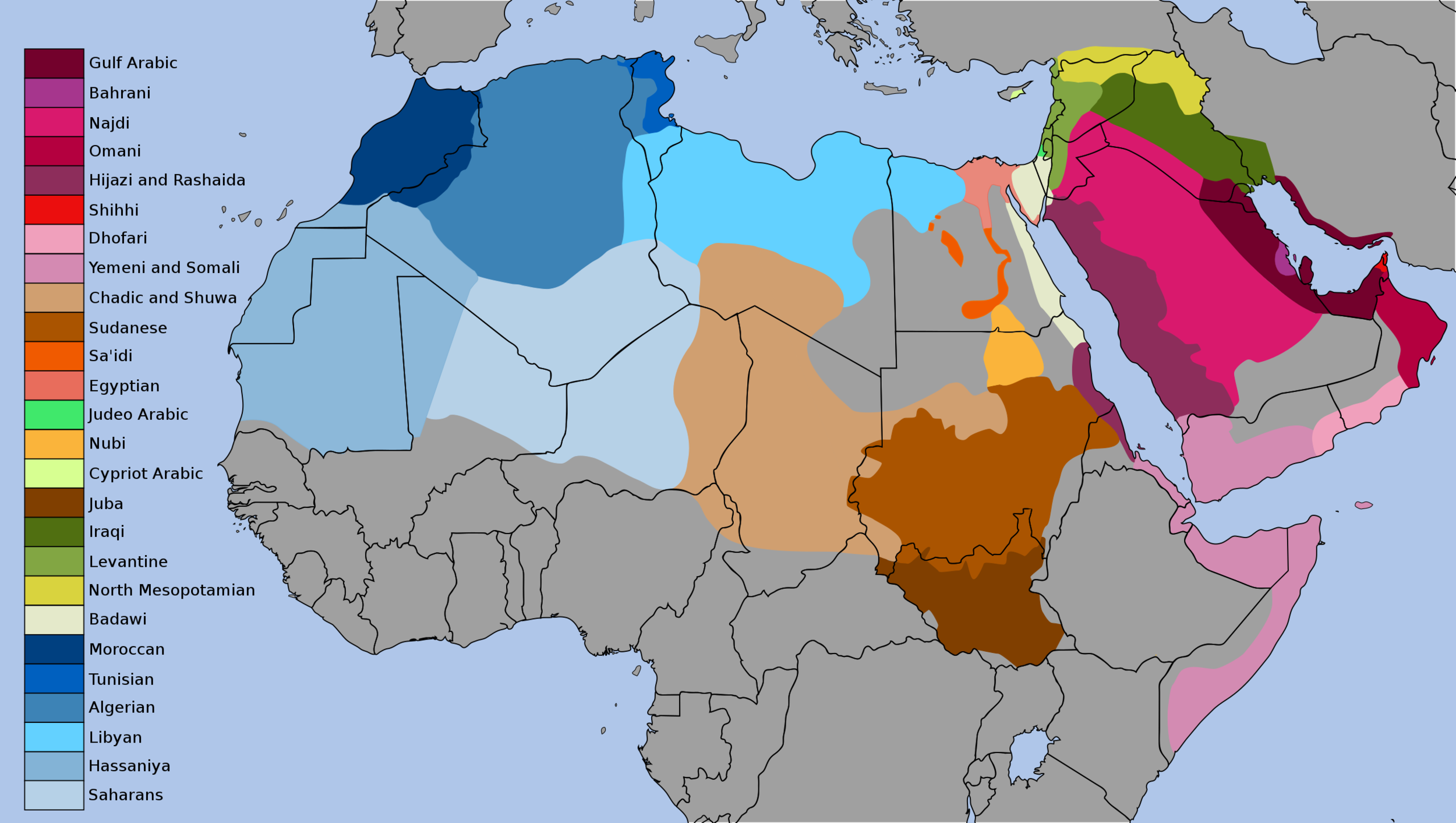

The Arabic language can be more accurately described as a cluster of around 30 individually recognized dialects roughly grouped into the following categories:

Literary or Classical Arabic: This is the language used in the Qur’ān and the religious language of Islam. It is uniform across all Arabic-speaking countries and has undergone relatively few changes from ancient times to the present day. Think of it as similar to Latin in the Catholic Church: No one speaks it, but plenty of people study and understand it in a religious context.

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA): This is the most widely used and understood form of Arabic in the world. Also referred to as “business Arabic,” it is the version of the language used by Arabic-speaking newscasters, journalists, and technical professionals. MSA is the official language of 26 countries and a handful of territories, and it is also a recognized minority language in 7 other countries. This is the dialect that non-native Arabic speakers are typically taught when they decide to learn Arabic.

Source: ResearchGate

Colloquial or Daily Arabic: These are four main groupings of informal dialects that are categorized by geographical location. While these groupings may differentiate between the pronunciation of words or even have different words or phrases to describe the same concept, these speakers are generally able to understand one another. The groupings are as follows:

Egyptian dialect: This dialect is spoken primarily in Egypt and is one of the predominant dialects spoken in Arabic television, movies, and popular culture. It draws a lot of influence from Turkish, Greek, Italian, and even English.

North African or “Maghrebi” dialects: This the Arabic spoken primarily in North Africa. Many of its speakers are also French speakers. Native Maghrebi speakers sometimes refer to their own language as darja or derja, which is a Maghrebi word that basically means “everyday language.”

Gulf Arabic dialects: These are the dialects spoken primarily on the Arabian Peninsula, particularly Bahrain, Kuwait, and parts of Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Iran. This is one of the most linguistically diverse groupings; speakers of one Gulf dialect may have a hard time understanding speakers of another Gulf dialect even though they are speaking the same language. Linguistically, Iraqi Arabic acts as a halfway point between the major Gulf dialects and the Levantine dialects.

Levantine dialects: These are the dialects spoken in Jordan, Palestine, and parts of Syria. After the Egyptian dialect, it is the second most commonly used regional dialect in Arabic popular culture. It is highly influenced by Aramaic, which is an Indigenous language in the region of Syria that is still spoken by scattered communities throughout the Middle East.

How are Arabic and English Similar?

Although all of this may seem strange to an English speaker, English actually has quite a few words that are derived from Arabic! Many of them refer to goods or other cultural exports since initially English-speaking civilizations usually interacted with Arabic-speaking civilizations through trade. Here are some examples:

alcohol (from the word al-kuḥul, meaning “a mixture of powdered antimony”)

magazine (from the word al-makhzan, meaning “a storehouse”)

sofa (from the word ṣūfā, meaning “a cushion”)

elixir (from the word al-iksīr, meaning “the philosopher’s stone”)

arsenal (from the phrase dār assilaḥ, meaning “house of weapons”)

algebra (from the phrase ‘ilm al-jabr wa'l-muqābala’, meaning “the science of restoring what is missing, and equating like with like”)

zero / cipher (both from the word ṣifr, referring to the mathematical concept of “empty” or “null”)

How does Arabic differ from English?

Like Romance languages, such as Spanish or French, but unlike English, all Arabic nouns have either a masculine or feminine gender, even nouns that don’t have a gender in the real world. For example, words like “mother” and “girl” are feminine nouns in Arabic, but so are words like “desert” and “car.” Similarly, words like “man” or “brother” are masculine nouns, but so are words like “sword” or “river.” Words that refer to people, such as “teacher” or “student,” can be feminine or masculine depending on the context.

Arabic and English have a number of similar consonants, but Arabic also has some consonants that are absent in English. Arabic speakers speaking English may replace English consonants in English words with a similar sound in Arabic; for example, Arabic has an “f” sound but no “v” sound, so they might say “fery” instead of “very.”

Arabic is also pronounced phonetically, whereas English is not, so an Arabic speaker might over-pronounce an English word with silent letters; for example, they might pronounce the word “tough” like “too-geh.”

The Arabic word for Egypt is Misr, or مصر.

Source: World Wide Web Consortium

One of the most significant differences between English and Arabic is that while English has letters that can be combined to form sounds and words, Arabic uses a script called abjad (pronounced AHB-zhahd) to represent sounds and words. Abjad is read from right to left on a page, as opposed to the way English is read from left to right.

All of the symbols in abjad, or what an English speaker would think of as “letters,” are the consonant sounds of the language. Vowels are written as different markings above or below the letters. Arabic is sometimes transliterated (or written with the English alphabet instead of abjad) but most Arabic writing uses abjad.

Source: Arabic Speak

A word written in abjad is made up of two parts: the consonants, or “root,” which give the word its vocabulary definition, and the vowels, or “pattern,” which give the word its grammatical meaning. For example, the root /k-t-b/ with the pattern /-i-ā-/ creates the word kitāb, which means “book,” but the same root with the pattern /-ā-i-/ creates the word kātib, which means “person who writes” or “clerk.”

What is important to an Arabic speaker’s culture based on their language?

Formality

Like many languages, Arabic has different levels of formality, and an Arabic speaker would use very different greetings or phrases with their employer than they would with a family member or close friend. Even in English, you probably wouldn’t greet an important business associate for the first time by saying “Hey, what’s up?”; you’d probably choose something like “Hello,” or even more formally, “Pleased to meet you.”

To say hello, an Arabic speaker would formally say “As-salāmu alaykum” (ahs-sah-LAH-muh ah-LAY-kuhm) or “Peace be upon you.” The appropriate response would be “Wa-alaykum s-salām,” (wah ah-LAY-kuhm sah-LAHM) or “And upon you, peace.” Informally, these two speakers might just say “Salām” to one another, which literally translates to “peace” and would be the equivalent of an English speaker saying “hi” instead of “hello.”

It is important to note that while these greetings, and many other Arabic phrases and sayings, uses a lot of religious imagery and references, they are used by non-Muslim (and even non-religious) Arabic speakers. For example, a common response to the question “How are you?” is “Alhamdulillāh” (ahl-HAM-duh leel-LAH) which means “I’m doing well,” but literally translates to “Praise be to God.” This is similar to how an English speaker might say “Bless you” when someone sneezes, regardless of religious intent.

How the Arabic Language Reflects the Importance of Family

Another common thread in Arabic terms and phrases is the importance of family and community. Even among groups of people who aren’t related to one another, such as coworkers, it is not uncommon for an Arabic speaker to address their colleagues as “brother” or “sister.” (This familiarity in the workplace often does not extend to a superior like a director or boss; an Arabic speaker would usually address that person with the Arabic equivalent of “sir” or “madam.”)

Because kinship and family ties are taken quite seriously in many Arabic-speaking Middle Eastern cultures, declaring someone to be close enough as to be considered a member of your family is a high honor.

Depending on the closeness of a relationship, an Arabic speaker might use a much more informal greeting instead of the formal “As-salāmu alaykum.” If these two speakers were quite close, they might exchange the phrases “Ahlan wa sahlan” and “Ahlan bik” with one another. This is a very warm greeting among close friends and family that is usually translated to “you are welcome here,” but carries a meaning that is more along the lines of, “you are among your people here.” Because of this intimacy, using “Ahlan” with someone that you are not close to can come off as presumptive or rude.

You may also hear your Arabic-speaking acquaintances referring to a fairly distant relative as close family. It is important to note that the typical Middle Eastern family unit is often structured differently than those in the West. It isn’t uncommon to find an Arab family in which aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents all live in the same house. Lineage is also important in many Middle Eastern cultures, so you’re likely to find unique Arabic words for family members that can be as specific as “my male cousin on my mother’s side.”

Conceptualizing Time

A miscommunication that may arise between Arabic and English speakers is in the way that both languages denote time of day. It is helpful that neither language uses the 24-hour military clock like many Romance languages do; however, Arabic does not denote time with a.m. or p.m. Rather, the language specifies “in the morning” or “at night.” Even this difference is not standard! For example, you might want to set up a meeting with someone at 2:00 p.m. In Arabic, you might phrase this time as “two hours after noon.” However, if your meeting is at 4:30 p.m., you might phrase this time as “half past four hours in the late afternoon.” Additionally, the concept of noon differs. In Arabic, noontime refers to a roughly 4 hour period from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., rather than strictly 12 p.m. as is the case for noon in English. Most Arabic speakers that live in the United States are knowledgeable enough of the a.m./p.m. distinctions, but it is still something to keep in mind when scheduling meetings, appointments, or trainings.

Additionally, it is good to note that there isn’t a direct Arabic translation for the concept of being late for an appointment, meeting, or shift. This is due to the fact that many Arab cultures are polychronic, which means that they tend to value personal relationships and will prioritize timeliness based on the importance of any given relationship. Many American business models (and businesspeople) are monochronic, which often values timeliness, procedures, and policies above personal circumstances. This is a generalization, of course, but it is good to note these cultural differences if you are trying to explain the importance of tardiness to any Arabic-speaking employees.

Proverbs

Even everyday Arabic uses a lot of poetic phrases and imagery, and this extends to frequent usage of proverbs and idioms as well. Several common themes that can be found in Arabic proverbs are emphasizing modesty, seeking knowledge and perspective, and expressing the importance of community and teamwork. While plenty of these proverbs come from the Qur’ān, the Muslim holy book, others are simply passed down as folk wisdom.

Here are the English translations of some common proverbs in Arabic cultures:

“Do good and cast it into the sea.” This proverb emphasizes humility when performing charitable acts, stressing the idea of doing good for the sake of itself rather than for recognition or reward.

“Excess is the brother of shortage.” This proverb, like the English phrase “too much of a good thing,” cautions against overindulgence and greed.

“A hand by itself does not clap.” Though this proverb has been adopted in Western cultures, it originates in many Arab cultures that value teamwork and collective success.

“Seek knowledge from the cradle to the grave.” This proverb is often used to encourage curiosity and creativity, in the same context as an English speaker might say “Seek and you shall find.”

“Even if your friend is honey, beware not to lick them all up.” This proverb cautions against taking advantage of the kindness of a loved one.

Let us know what you found interesting, what languages you would like to learn about next, or if you have any fun facts to share about the Arabic language! Make sure to subscribe to receive notifications for future posts in this series.

If you read something in this post that you would like to discuss, suggest a correction for, or make a comment on, please email us at comment@gogyup.com.