Health Literacy and Dyslexia: How Technology Increases Awareness

Written by Ned Zimmerman-Bence, Co-Founder of GogyUpOctober is a crowded month for celebration and awareness. Of the many important causes that seek increased public awareness this month, three stand out for us because they intersect at the heart of GogyUp's mission and highlight the role of technology in improving life and society:

But before we ramble on, we should be clear that our understanding of each of these causes continues to develop. Just like any group of inquisitive learners, we are not free from making mistakes as we learn. If you read something in this post that you would like to discuss, suggest a correction for, or make a comment on, please email us at comment@gogyup.com.

For the remainder of this post, we will focus on the intersection of dyslexia, technology, and health literacy - picking up with NDEAM next week.

Dyslexia and Dyslexia Awareness Month

According to the International Dyslexia Association, developmental dyslexia (commonly simplified to dyslexia) is a specific learning disability with neurobiological origins "characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge."

Despite the widely-held, simple and false notion that dyslexia is a reading problem centered around "switched or backwards letters", dyslexia is complex with effects that extend beyond reading.

As recognition grew that 80-90% of all individuals with a learning disability and 20% of the general student population may be impacted by a form of dyslexia, a bipartisan resolution with unanimous consent by the U.S. Senate established National Dyslexia Month in October 2015. Its purpose: "to recognize the significant educational implications of dyslexia that must be addressed by The Nation's Congress, schools, state and local educational agencies."

As public response to dyslexia grew, research and clinical knowledge also continued to grow. Dyslexia is now understood to exist across a continuum, to encompass and impact a broad range of cognitive functions in varying degrees:

phonological processing (i.e., the ability to hear, process, separate, and remember sounds)

memory, particularly time-based memory

executive function (i.e., the ability to plan and coordinate future actions)

To further capture dyslexia's complexity, researchers are beginning to recommend that a dyslexia diagnosis be classified into one (or more) different types:

"Classic" or phonological

Non-verbal or visual-attentional

Dyspraxic (e.g., motor coordination required for legible handwriting)

In short, dyslexia is:

a neurobiological condition affecting up to 20% of the U.S. population,

that impacts multiple cognitive functions including phonological processing, memory, and executive functioning to varying degrees in different individuals,

and can "appear" differently in different individuals.

How Technology Revealed and Continues to Inform About Dyslexia

Language and literacy are deeply intertwined, yet language evolves organically while the written word (i.e., encoding language into text) developed primarily through the application of technology: from clay tablets, styli, papyrus, brushes & ink, parchment, paper, moveable type, the printing press, lithography, and the typewriter, to today's "auto-complete" features such as Google's Smart Compose. The expanding adoption and development of technologies not only increases the availability of diverse information, they also standardize how that information is conveyed. One only needs to compare the variety of different spellings that occurred before printed dictionaries and how those spelling eventually became standardized as dictionaries became more prevalent. Reading and, by extension, literacy is a process for decoding language captured by an invented process: the written word (a technology).

Reading, technology, and dyslexia are similarly intertwined. The first observation of a "word blindness" is attributed to Adolph Kussmaul, a German Professor of Medicine at Strassburg. Another German, the ophthalmologist Rudolf Berlin, also noticed the inability of some patients to read written words even though there was no problem with their vision. Berlin coined the term "dyslexia" in 1877 as British physicians also began studying this "word blindness" in children. This initial diagnosis and research into dyslexia coincided with the implementation of public education and mass teaching of reading (i.e., the process for decoding the printed word - a technology) as one of its foundational skills. As reading became a skill increasingly central to daily life and economic activity, access to the printed word expanded as did research into why a portion of the population were unable to reliably learn to read. The "word blindness" condition had not been detected until a technology (i.e., printed language) became widely implemented through public education to convey civic information and knowledge and the process of reading became central to daily and economic life.

Interestingly, another technology central to understanding dyslexia, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), began developing almost in parallel with knowledge about dyslexia. First conceived by Nikola Tesla in 1882, MRI technology continued to develop and in the late 1990s began to allow researchers to observe in realtime how different conditions, including dyslexia, may impact brain function.

But while awareness about dyslexia continues to grow thanks to efforts like Dyslexia Awareness Month and technology continues to deepen understanding and identify potential solutions or accommodations for dyslexia, the condition presents significant barriers for people with a dyslexic diagnosis as well as the potential millions who may need those solutions and accommodations to obtain, process, and understand critical information necessary to thrive in an industrialized country in the information age.

Health literacy is a prime example.

Health Literacy and Health Literacy Month

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Service defines health literacy as "the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions."

This composite story illustrates why health literacy is important:

Sherry, 53, is referred to a clinic for care following a four-week hospitalization. Upon discharge, she is provided with a handwritten list of medications. When asked by clinic staff why she was admitted, Sherry says, “I had a bad cold.” Her hospital records, however, show an admission for pneumonia complicated by congestive heart failure and diabetes. Although Sherry’s hospital physicians said they communicated these diagnoses, she left the hospital without a full understanding of her condition.

Per the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: "Every October, we celebrate Health Literacy Month — a time to recognize the importance of making health information easy to understand and the health care system easier to navigate." As Sherry's profile shows, "making health information easy to understand" is a tall order especially when considering 80 million U.S. adults are thought to have low health literacy. Sherry's lack of understanding and knowledge means she is likely to be poorly equipped to manage her disease and could very well experience less than optimal health outcomes. Her statement, "I had a bad cold", may in fact belie an internal unease about her vague understanding of the severity of her illness.

It should also be emphasized that the discharging hospital was not acting as a "health literate" organization and failed to ensure that Sherry had a proper level of understanding before discharging her.

Where Dyslexia and Health Literacy Could Intersect

The National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy identifies several strategies to improve health literacy and reduce health disparities, including an emphasis on general print literacy - the ability to read and understand complex medical information. Despite the potential size of the dyslexic population and the large number of adults with low health literacy, there is alarmingly little research on dyslexia's impact on health literacy and patient education. Yet, the 30 years of research on patient education materials highlights the disconnect between those materials and many patients' capacity to understand them.

Reconsidering Sherry, almost anyone would be overwhelmed by a list of unfamiliar medications with potentially different dosing instructions and oral communications regarding her recent illness when coupled with her long-term complex disease. Increased health literacy might have minimal immediate impact given the complexity of her case, but without greater health literacy her health outcomes might not improve, negatively impacting her quality of life. Without knowing Sherry's ability to read or whether she is dyslexic and therefore requires additional accommodations beyond clearly written instructions, her capacity to appropriately manage her condition is unknown and a positive health outcome in doubt.

Remember, dyslexia is not simply a reading disorder, but rather a neurobiological condition that affects a number of cognitive functions necessary for understanding, including executive functioning (the ability to plan and coordinate future actions) and time-based memory (required to execute tasks at specified future points). The limited research that does exist identifies significant non-compliance with medication in dyslexic patients. Considering the scale of adult illiteracy (38 million working-age adults), the potential number of adults with a form of dyslexia (20%), and the significant proportion of the U.S. adult population classified as "low health literacy" (80 million), it stands to reason that dyslexia awareness among health care providers and accommodations to facilitate health literacy in the dyslexic population would have significant, beneficial spillover effects to the other individuals who have low print literacy or English proficiency.

Our Potential Role: Diabetes Patient Education

Current methods such as teach-back and including interpreters in medical appointments make information accessible during the appointment. However, positive effects fade after the appointment. Given the impact dyslexia has on memory, and time-based memory in particular, health information needs to be accessible to patients with limited literacy or English proficiency in-the-moment. Given that over 30 years have passed since print materials were recognized to be too complex, goals to reduce the complexity of patient education materials are admirable but may be unrealistic. The situation is further compounded by increasingly complex treatments and more sophisticated and prevalent misinformation.

As a company focused on developing assistive-reading technology that raises the capacity of all adults to understand information in-the-moment, we are energized by the potential to be a bridge between health providers and their patients. Exacerbating the difficulty of print materials are endemic barriers that further impede patients’ capacity for health literacy (ability to process health information to make decisions), including low print literacy, limited English proficiency, and undiagnosed dyslexia.

We are gratified that the National Institute of Nursing Research agrees that GogyUp has the potential to be such a bridge. This fall, the Institute awarded GogyUp and our partners at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, School of Medicine and the Community University Health Care Clinic a SBIR Phase I grant to provide in-the-moment support for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patient information via our assistive-reading technology. During the grant, patients will have access to the same patient education materials that are normally available but they will be incorporated into the GogyUp mobile platform. By using GogyUp's personalized, assistive-reading technology with their patient education materials, the platform will be able to provide in-the-moment support for patients’ capacity to read and understand difficult written materials necessary to understand and successfully adhere to their T2DM self-care management plan. Meanwhile, clinicians and health educators can get real-time end-user data on how well their materials are understood and be able to revise and adjust as necessary to adapt to an individual's and cohort's specific needs.

Launching towards the end of Dyslexia Awareness Month and Health Literacy Month, the study will hopefully become a highly scalable case study for how technology can inform and ultimately mitigate the impact of dyslexia on one's health literacy and, by extension, one's quality of life.

A one-pager describing the study is available here.

If you are connected to a clinic that may be interested in participating in our study, please contact Ned Zimmerman-Bence: ned.zb@gogyup.com

Resources for Getting Involved

Here are a few resources that were informative in developing our thinking and writing this post. Do you have others that should be on this list? Please send them to comment@gogyup.com.

Dyslexia Awareness

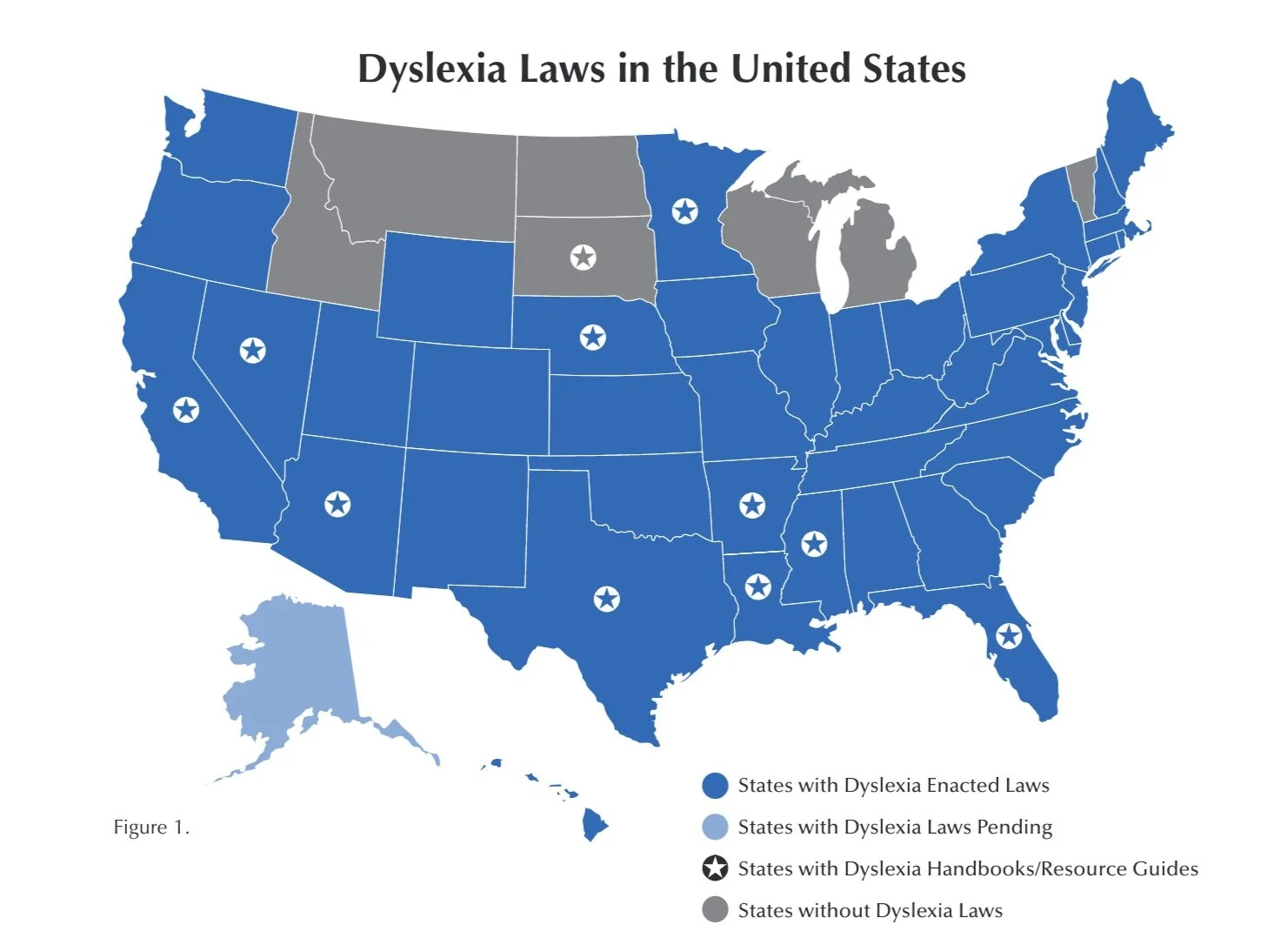

Track dyslexia legislation in your state: go to International Dyslexia Society and scroll to the bottom.

Read the excellent research briefs produced by the National Center on Improving Literacy to get up-to-speed on the latest dyslexia research.

Find a group to join or support through Decoding Dyslexia.

Health Literacy

Learn from the Institute for Healthcare Advancement's free, online health literacy training.

Join or support an organization promoting health literacy in your state.

Sources

Baumann, G. (Ed.). (1986). The Written word: Literacy in transition. Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press.

British Library. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://www.bl.uk/history-of-writing/articles/a-brief-history-of-writing-materials-and-technologies

CDC. (2021, August 11). Attributes of a Health Literate Organization. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/planact/steps/index.html

Davis, T. C., Crouch, M. A., Wills, G., Miller, S., & Abdehou, D. M. (1990). The gap between patient reading comprehension and the readability of patient education materials. The Journal of Family Practice, 31(5), 533–538.

Definition of Dyslexia—International Dyslexia Association. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://dyslexiaida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/

Eliez, S., Rumsey, J. M., Giedd, J. N., Schmitt, J. E., Patwardhan, A. J., & Reiss, A. L. (2000). Morphological Alteration of Temporal Lobe Gray Matter in Dyslexia: An MRI Study. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41(5), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00650

The Three P’s: Papyrus, Parchment and Paper | Rare Books & Manuscripts. Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://www.adelaide.edu.au/library/special/exhibitions/cover-to-cover/papyrus/

Habib, M. (2021). The Neurological Basis of Developmental Dyslexia and Related Disorders: A Reappraisal of the Temporal Hypothesis, Twenty Years on. Brain Sciences, 11(6), 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060708

Hickey, K. T., Creber, R. M. M., Reading, M., Sciacca, R. R., Riga, T. C., Frulla, A. P., & Casida, J. M. (2018). Low health literacy. The Nurse Practitioner, 43(8), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NPR.0000541468.54290.49

Kirby, P. (2020). Dyslexia debated, then and now: A historical perspective on the dyslexia debate. Oxford Review of Education, 46(4), 472–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1747418

Melby-Lervåg, M., Lyster, S.-A. H., & Hulme, C. (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 322–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026744

National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy | Health Literacy | CDC. (2020, February 20). https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/planact/national.html

Patra, S. (2021, January 8). A Brief History Of Reading Through The Ages. BOOK RIOT. https://bookriot.com/history-of-reading/

Perspectives on Language Winter 2019. (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://mydigitalpublication.com/publication/?i=572951&view=issueViewer&pp=1

Rea, A. (n.d.). How Serious Is America’s Literacy Problem? Library Journal. Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://www.libraryjournal.com?detailStory=How-Serious-Is-Americas-Literacy-Problem

Ritter, A., & Ilakkuvan, V. (2019). Reassessing health literacy best practices to improve medication adherence among patients with dyslexia. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(11), 2122–2127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.05.024

Smith-Spark, J. H., Zięcik, A. P., & Sterling, C. (2016). Time-based prospective memory in adults with developmental dyslexia. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 49–50, 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.006

The History of English: Spelling and Standardization (Suzanne Kemmer). (n.d.). Retrieved October 6, 2021, from http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~kemmer/Histengl/spelling.html